John McCarthy: The Generational Clash Behind the Birth of 'Artificial Intelligence'

In the annals of computer science, few names resonate as profoundly as John McCarthy. Often hailed as the ‘father of Artificial Intelligence,’ McCarthy not only conceptualized the field but also gave it its enduring name. The year was 1956 when he formally introduced the term ‘Artificial Intelligence’ for the landmark Dartmouth Conference, setting the stage for a revolution. Yet, the path to establishing this groundbreaking discipline was far from smooth, marked by conceptual battles and a notable ‘generational clash’ that foreshadowed the need for such a distinct definition.

The Genesis of a Term: Beyond Classical Automatics

Before the iconic 1956 Dartmouth Workshop, where the term ‘Artificial Intelligence’ made its official debut, McCarthy was grappling with a fundamental disconnect. His vision involved machines that could mimic human thought processes, solve complex problems, and engage in abstract reasoning – a stark departure from the prevailing technological paradigms of the time. The existing vocabulary, heavily rooted in ‘classical automatics,’ cybernetics, and control theory, simply couldn’t encapsulate the ambitious scope of what he envisioned.

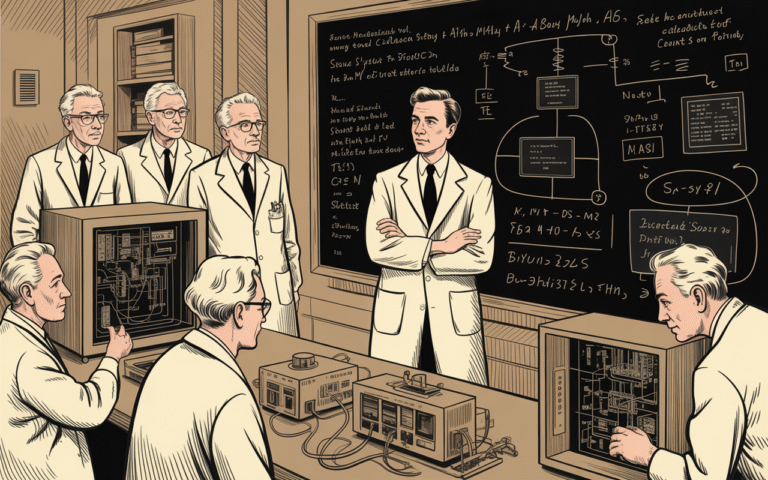

The 1952 Bell Labs Predicament: A Clash of Visions

The core of this early friction came to a head during McCarthy’s time at Bell Labs in 1952. While his colleagues were deeply immersed in refining systems for automation, control, and signal processing – highly sophisticated yet fundamentally deterministic tasks – McCarthy was dreaming bigger. He sought to imbue machines with the capacity for *thinking* in a more human-like, abstract sense. This divergence led to a significant ‘generational clash’ where his forward-thinking ideas were met with considerable skepticism. The established researchers, masters of their domain, found it challenging to grasp or even accept the premise of machines thinking, as it fell outside the well-defined boundaries of their engineering disciplines.

This early resistance was critical. It highlighted a void in the scientific lexicon – there was no appropriate term to differentiate McCarthy’s nascent field from the more tangible, mechanistic goals of ‘automatics.’ The skepticism wasn’t malicious but stemmed from a paradigm mismatch: one group focused on refining existing, predictable systems, while McCarthy aimed to create something entirely new and conceptually challenging.

Forging a New Discipline: The Imperative for ‘AI’

The experiences like the one at Bell Labs underscored the urgent need for a precise, distinct term. By 1956, when he was organizing the Dartmouth conference, McCarthy realized that to unify and define this disparate new area of research, a fresh label was indispensable. ‘Artificial Intelligence’ served not just as a name, but as a declaration – a clear demarcation from traditional computer science and engineering, asserting a new frontier where machines would transcend mere computation to emulate intelligence.

This strategic naming helped to legitimize the field, providing a banner under which researchers could rally, secure funding, and carve out a distinct academic and scientific identity. Without a unique term, the groundbreaking work of McCarthy and his contemporaries might have remained subsumed under existing, less ambitious disciplines.

John McCarthy’s foresight, both in conceiving the potential of machine intelligence and in strategically naming it, was pivotal. The early skepticism and the ‘generational clash’ he faced were not mere roadblocks but catalysts that reinforced the necessity of a bold new definition. His struggles at Bell Labs in 1952 perfectly illustrate the challenges inherent in introducing revolutionary concepts, paving the way for ‘Artificial Intelligence’ to emerge as one of the most transformative fields of the 21st century.